Description

Homer Dodge Martin (1836-1897)

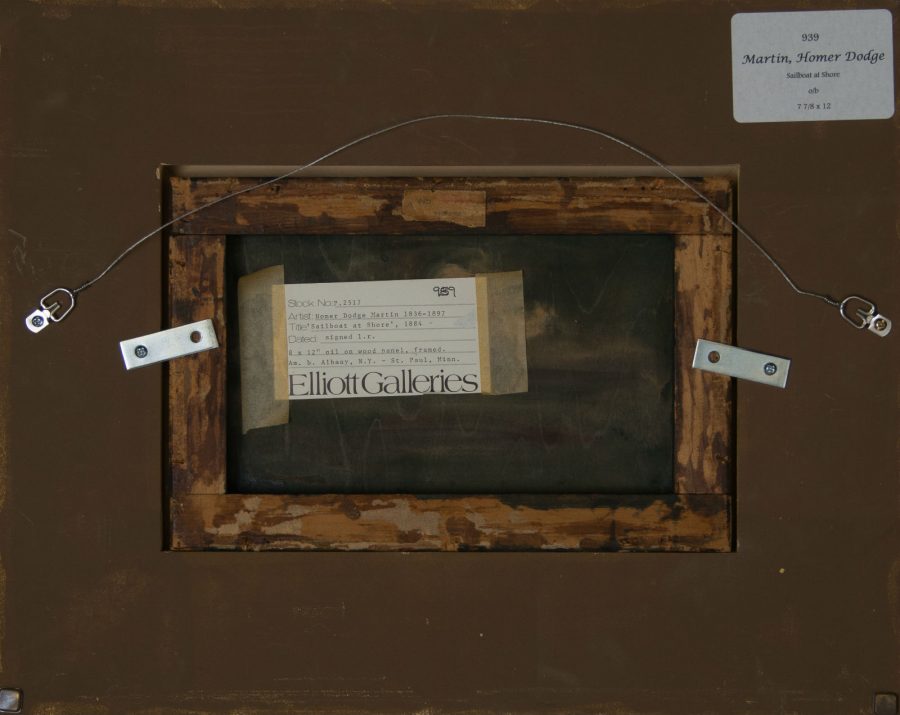

Condition Report: Both painting and frame are in good condition. Signed lower right. Titled on Verso by Elliot Galleries “Sailboat at Shore” 1884

Provenance: Elliot Galleries

Biography from the Archives of askART

Born in Albany, New York, the same year as Alexander Wyant, on 28 October 1836, Martin forged a career that spanned the Hudson River School style to more of a plein-air style that approximated impressionism. Popular with the earlier critics, Martin was praised with hyperbole: “his finest canvases looked as if no one but God and he had ever seen the places pictured” (Sherman, 1917, p. 4) but was justly allocated a respectful place in the pantheon of American landscape painters. Martin was the son of Homer Martin and Sarah Dodge. Martin’s future wife Elizabeth verified that he made drawings as a child (Martin, 1904, pp. 4-5) and a lot of what he learned was self-taught. Erastus Dow Palmer, the sculptor, recognized Martin’s talent and invited him to attend a salon of artists that included George Boughton (1833-1905), William Hart (1823-1894) and James M. Hart (1828-1901).

By 1857, Martin began sending works to the National Academy of Design. Two years later, he was working in the Tenth Street Studio Building. He married Elizabeth Gilbert Martin on 25 June 1861. Homer Dodge Martin began painting in a detailed Hudson River School style, then gradually suppressed detail until he became known for his “power to wrest from the scene before him its very heart, to seize the essential – the elemental” (Meyer, 1908, p. 255). Part of this new simplification resulted from the influence of John F. Kensett, whom he met in the Tenth Street Studio. Mather (1912, pp. 37-38) pointed out how Martin “was the only painter intelligent enough” to realize that Kensett was an artist worth imitating. But Martin, “one of the Corot worshippers from the first,” according to his wife, underwent the Barbizon influence during a trip to Europe in 1876. In addition, Martin met Whistler in London. Consequently, in the late 1870s, Martin’s works “reveal the influence of both Whistler and Corot in the choice of small forest scenes, increased freedom of handling, and concentration on tone. . . .” (Spassky, 1985, p. 421). Another voyage abroad followed: between 1881 and 1886 he remained in France, mainly in Normandy (Villerville). Mrs. Martin (1904, p. 39) called the trip to France her husband’s “seed-time” where his artistic concepts germinated.

Martin turned to more saturated color, more flowing contours, and he even used a palette knife (Spassky, 1985, p. 421). The Mussel Gatherers (Corcoran Gallery of Art), dated 1886, most likely painted in Normandy, shows a broad, painterly technique. After his return home in December of 1886, Martin continued to exhibit his works but made only enough from sales to get by. Martin was active in the Society of American Artists, whose members believed his work fulfilled the requirements of the SAA’s “higher standard of art.” (Low, 1908, p. 245). From his late period (the 1890s) we have more than one masterpiece: one of these, Honfleur Light (1890-92) in the New York Century Club, composed of a very limited palette, is close in spirit to Whistler’s Crepuscule in Flesh Color and Green: Valparaiso (Tate Gallery, London, 1866). Bermingham (1965, p. 61), in fact, pointed out that when Martin visited Whistler’s studio in 1876, he may have been struck by Whistler’s works of the mid 1860s.

Perhaps Martin’s most famous work is View on the Seine: Harp of the Winds (Metropolitan Museum of Art), from 1895, conceived from a sketch. Although influence from Monet seems likely – Martin may have seen Monet’s one-man show at Durand-Ruel in 1886 – Spassky (1985, p. 425) explains why View on the Seine is not an impressionist work: “Martin was not concerned with either the immediacy of the image or with the fugitive effects of light. Instead, his composition reflects prolonged contemplation. It is constructed tonally, with the focus on a few silhouetted motifs.” The landscape is pure tonalism with broken brushwork in the reflected poplar trees, which could be mistaken for broken color. The title could easily be related to Walter Pater’s dictum that art aspires to the condition of music. Caffin (1907-A, p. 204) believed that Martin’s defective eyesight contributed to his use of imprecise contours, but the effect of View on the Seine is not really unexpected from a great emulator of Corot. There is a similar lyricism and golden-toned nostalgia in the oeuvre of both artists who were considered to be “children of nature.” Mather (1912, p. 35) insisted, however, that Martin “retained his love of color, never sacrificing it to tone in the manner of Corot,” and Laurvik (1915, p. 19) detected luminous and multi-colored shadows in Martin’s Saranac Lake, which he likened to “the early manner of Claude Monet.”

Four of Martin’s works were featured in the World’s Columbian Exposition. It is unfortunate that after 1894, the year that William T. Evans purchased two of the artist’s works, Martin was unable to find buyers for later paintings (Meyer, 1908, p. 262). The painter died in St. Paul, Minnesota on 12 February 1897; three years later, his Westchester Hills sold for $5,300, the highest price ever fetched for an American painting. Unfortunately for current Martin scholars, Patricia Mandel’s dissertation on the painter remains “restricted.” Martin is certainly a name worth reviving.

Sources:

“American Painters – Homer D. Martin.” Art Journal 6 (November 1880): 321-323; Caffin, Charles. American Masters of Painting. New York: Doubleday and Co., 1902, pp. 115-128; Martin, Elizabeth. Homer Martin: A Reminiscence. New York: William Macbeth, 1904; Caffin, Charles. The Story of American Painting. New York: Frederick A. Stokes Co., 1907, pp. 203-213; Low, Will. A Chronicle of Friendships 1873-1900. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1908, pp. 242-246; Meyer, A. Nathan. “Homer Martin: American Landscape Painter.” International Studio 35 (October 1908): 255-262; Mather, Frank Jewett. Homer Martin: A Poet in Landscape. New York: 1912; Carroll, Dana H. Fifty-eight Paintings by Homer D. Martin. New York: 1913; Laurvik, J. Nilsen, in Catalogue de Luxe of the Department of Fine Arts, Panama-Pacific International Exposition. Ed. John E.D. Trask and J. Nilsen Laurvik. San Francisco: Paul Elder and Co., 1915, pp. 18-19; Sherman, Frederic Fairchild. “The Landscape of Homer Dodge Martin.” Art in America 3 (October 1915): 66-70; Neuhaus, Eugen. The Galleries of the Exposition. San Francisco: Paul Elder and Co., 1915, p. 56; Sherman, Frederic Fairchild. Landscape and Figure Painters of America. New York: 1917, pp. 3-9; Idem, “The Later Canvases of Homer Dodge Martin.” Art in America 7 (October 1919): 255-260; Van Dyke, John C. American Painting and Its Tradition. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1919, pp. 67-87; Jackman, Rilla Evelyn. American Arts. New York: Rand McNally and Co., 1928, pp. 75-76; LaFollette, Suzanne. Art in America: From Colonial Times to the Present Day. New York: W. W. Norton and Co., 1929, pp. 192-194; Neuhaus, Eugen. The History and Ideals of American Art. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 1931; Born, Wolfgang. American Landscape Painting. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1948, p. 167; Barker, Virgil. American Painting: History and Interpretation. New York: Macmillan, 1950, p. 602; Clark, Eliot. History of the National Academy of Design. New York: Columbia University Press, 1954, pp. 126, 391; Hoopes, Donelson F. The American Impressionists. New York: Watson-Guptill, 1972, pp. 28-29; Mandel, Patricia C. “Homer D. Martin: American Landscape Painter (1836-1897).” Diss., New York University, 1973; Idem, “The Stories behind Three Important Late Homer Dodge Martin Paintings.” Archives of American Art Journal 13 (1973): 2-8; Boyle, Richard J. American Impressionism. Boston: New York Graphic Society, 1974, pp. 74-77; Bermingham, Peter. American Art in the Barbizon Mood. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1975, pp. 58-63, 157-158; Howat, John and Natalie Spassky. The Heritage of American Art: Paintings from the Collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art. New York: The American Federation of Arts, 1975, pp. 142-143; Stebbins, 1976-B; Wilmerding, John. American Art. Pelican History of Art Series. Harmondsworth, Middlesex, UK and New York: Penguin Books, 1976, pp. 153-154; Brown, Milton W. et al. American Art. New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1978, p. 309; Sellin, David. Americans in Brittany and Normandy 1860-1910. Phoenix, AZ: Phoenix Art Museum, 1982, pp. 188-189; Gerdts, William H., Diana Dimodica Sweet, and Robert R. Preato. Tonalism: An American Experience. New York: Grand Central Art Galleries, 1982, pp. 74, 85; Spassky, Natalie. American Paintings in the Metropolitan Museum of Art. New York: 1985, pp. 420-430; Weber, Bruce and William H. Gerdts. In Nature’s Ways: American Landscape Painting in the Late Nineteenth Century. West Palm Beach, FL: Norton Gallery of Art, 1987, cat. no. 44; Baekeland, Frederick. Images of America: The Painter’s Eye, 1833-1925. Seattle, WA: University of Washington Press, 1991, p. 63; Point of View: Landscapes from the Addison Collection. Andover, MA: Addison Gallery of American Art, Phillips Academy, 1992, pp. 38, 142; Strazdes, Diana et al. American Paintings and Sculpture to 1945 in the Carnegie Museum of Art. New York: Hudson Hills Press, 1992, pp. 342-343; Revisiting the White City: American Art at the 1893 World’s Fair. Hanover and London: University Press of New England, 1993, pp. 283-284; Coen, Rena Neumann. Minnesota Impressionists. Afton, MN: Afton Historical Society Press, 1996, pp. 78-80; Fischer, Diane Pietruca. Paris 1900: The “American School” at the Universal Exposition. Exh. cat. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1999, pp. 74, 77, 80, 200; Prelinger, Elizabeth. American Impressionism. Treasures from the Smithsonian American Art Museum. New York: Watson-Guptill, 2000, pp. 62-63.

Submitted by Richard H. Love and Michael Preston Worley, Ph.D.

Reviews

There are no reviews yet.